Archaeologists from Egypt and Germany have discovered the remains of an ancient Egyptian statue they believe could depict one of history’s most famous rulers, Ramses II. Who was Ramses II? Ramses II led Egypt for 66 years, an astonishingly long reign in the ancient world when entire lifespans rarely lasted that long, and royal reigns were often short and brutal. “The growth and prosperity seen in Egypt at the time earned him the title ‘Ramses the Great.’” Later pharaohs referred to him as the “Great Ancestor.” His mummy, originally interred in the Valley of the Kings, now rests in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum.

Ramses II expanded the Egyptian empire’s reach as far north as modern-day Syria and as far south as modern-day Sudan. He negotiated a non-violent agreement establishing stable borders with the neighboring Hittite Empire, marking the first peace treaty in history. When you think of ancient Egypt, you’re likely picturing Ramses II. He commissioned buildings all over Egypt, and his cartouche and stylized features adorn most of them. His face is on the colossi at Abu Simbel, and many sculptures and inscriptions at the Ramesseum (his memorial complex) are variations of the Great Ancestor.

Ramses II is often associated with the biblical “pharaoh of the Exodus,” who ruled Egypt when thousands of Israelite slaves escaped across the Red Sea. However, there is no reliable evidence for this. Some ancient Greek sources refer to Ramses II as Ozymandias, the poetic name Percy Shelley used in his famous sonnet. “Ozymandias” was inspired by ruined busts of Ramses II at the Ramesseum and a description of the statues from an ancient Greek historian: “King of Kings Ozymandias am I. If any want to know how great I am and where I lie, let him outdo me in my work.” Next to Cleopatra and King Tut, Ramses II is probably the most famous pharaoh in Western pop culture. He is the main character, for instance, in Anne Rice’s novel The Mummy, or Ramses the Damned, and Norman Mailer’s Ancient Evenings, and provides inspiration for the alter ego (Ozymandias) of the antagonist in Alan Moore’s Watchmen series.

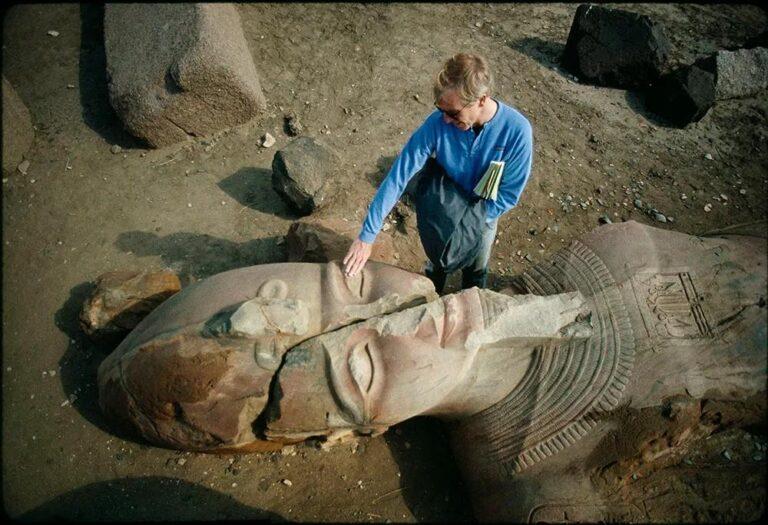

The newly discovered colossus may end up looking something like this—a statue of Ramses II unearthed in Tanis, Egypt. Both statues feature the telltale hedjet, the bowling-pin-shaped white crown of Upper Egypt.

The newly discovered statue has no inscription. Why do many archaeologists think it might be Ramses II? Three thousand years ago, the Matariya suburb was part of the city of Heliopolis. Heliopolis was the center of worship for the Egyptian sun god, Re (probably better known as Ra). Ramses was named after Ra (Ra-msj-sw, roughly meaning “born of Ra”) and dedicated dozens of temples and other buildings to the deity. As recently as 2006, archaeologists discovered one of the largest sun temples in Cairo under a marketplace. It was found to house a number of statues of Ramses II weighing as much as five tons. One such statue depicted the pharaoh seated and wearing a leopard’s skin, indicating that he might have served as a high priest of Re when the temple was built.

Ra was associated by ancient Greeks with their own god Helios, the personification of the sun. Heliopolis is a Latinized form of a Greek name for an Egyptian city. (Language is geography!) The city’s native name was I͗wnw—but pronunciation is uncertain even among Egyptologists. A limestone statue of Seti II, the grandson of Ramses II, has already been found at the Heliopolis site.

How did such a massive statue remain lost for 3,000 years? The Heliopolis site has been plundered for centuries, and the remaining rubble largely ignored. A better question might be “why did this statue survive”? The lead archaeologist at the Heliopolis site said the statue “might have been destroyed by early Christians or by the Muslim rulers of Cairo in the 11th century as they used limestone stonework from ancient temples to build the city’s fortifications. But statues like the colossus were cast aside because they were made from quartzite.” The dig site was established in 2012, ahead of a redevelopment project that will erect new buildings on top of the site. “It’s a race against time,” says one Egyptologist. In addition, a “rising water table, industrial waste, and piling rubble have made excavation of the ancient site difficult.” Remember—what is now Cairo and its suburbs is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. Thousands of unknown ancient sites sit beneath the vibrant, busy, modern city.